A woman shot and killed in her grandmother’s Valley Station home. A man dead of a suspected overdose in his sister’s home in Pleasure Ridge Park. A woman who told police she was strangled to the point of losing consciousness after refusing to have sex with her ex-boyfriend, who she still lived with.

In each of these cases, Louisville Metro Police officers responded. And each time, they decided the home — where the domestic violence victim or grieving loved ones lived — ought to be deemed a “public nuisance.”

Louisville’s public nuisance ordinance is intended to provide a way to bust up drug houses and crime dens. But police and code enforcement officials have been increasingly focused on residential locations where crimes are reported — regardless of whether the victim or the offender lives there.

While some nuisance cases involve stereotypical drug houses where drugs are manufactured or sold in high quantities, many stem from simple possession of drugs, paraphernalia or low-level trafficking offenses, a KyCIR review of nearly three years worth of nuisance cases shows.

In at least three dozen cases since 2017, the nuisance cases have stemmed from domestic violence, often putting housing at risk for victims in addition to perpetrators.

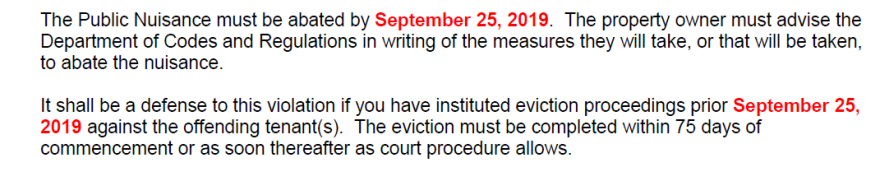

For renters, this has huge ramifications: after LMPD asks Louisville Metro Department of Codes and Regulations to issue a nuisance violation, its office sends a registered letter to property owners. The letter says the property has been deemed a public nuisance, and offers a defense: evict the tenants within 75 days.

If they don’t abate the issue, property owners face civil penalties starting at $400 and criminal fines as high as $1,000 a day, according to the letter.

The review shows that city agencies aren’t always following the terms of the ordinance, which requires two police interactions within a year before action is taken. Records show that, while city officials say the registered letter is just a warning, the code enforcement department is informing property owners the property has already been deemed a nuisance in that letter, and landlords are evicting tenants in response.

And the violations are issued seemingly randomly, given that the 200-plus violations issued this year don’t come close to the number of eligible police interactions in Louisville.

This is “utterly sickening,” said Councilwoman Jessica Green, a Democrat who represents District 1 in west Louisville.

Green voted for expanding the ordinance in both 2017 and 2018. She said she thought the ordinance was intended to go after businesses, and she had no idea how it’s been implemented.

“The application of this goes beyond decency and really common sense,” Green said. “This is a travesty, a real travesty.”

Officials from code enforcement and LMPD both said they’d examine how their enforcement is affecting victims of crime after learning of KyCIR’s findings. But they otherwise defended their use of the ordinance as a tool to address problem properties.

Codes and Regulations Director Robert Kirchdorfer said the nuisance ordinance is key to addressing problems for residents who live near homes with criminal activity. People might begin to reevaluate their lives if they’re forced to move every time they get in trouble, Kirchdorfer said.

And LMPD spokesperson Jessie Halladay said the ordinance is a creative and important tool that goes beyond “locking people up.”

“We can go in and make those arrests or do those citations, but then you just leave the environment there,” Halladay said.

But local housing experts and advocates for victims of violence said treating eviction like a crime-fighting device is bad policy that leads to housing instability for the city’s most vulnerable.

Nearly all nuisance cases come at the request of the Louisville Metro Police Department.

“This is insidious that we’re using the police force to evict people,” said Cathy Hinko, executive director of the Metropolitan Housing Coalition. “It doesn't seem to fit in with everything else that we're trying to do in Louisville to help stabilize families and people.”

It’s unclear how many nuisance cases led to an eviction because code enforcement officials don’t track the outcomes. At least 20 cases reviewed by KyCIR included documentation that a tenant was evicted, but homeowners don’t always submit the documentation.

Jerimy Austin, the city’s code enforcement supervisor, estimates at least half of all nuisance cases result in an eviction.

And enforcement of the ordinance is ramping up: police and code enforcement officials have issued more nuisance violations this year than they did in the previous two years combined.

Most Crimes Now Eligible As 'Nuisance'

Louisville’s public nuisance ordinance has been in place for decades, but for much of its history, it focused on prostitution, alcohol, gambling and felony drug offenses.

In 2015, Metro Council added parameters for which hotels and motels would be considered nuisances. It also added murder and assault to the list of crimes that justify a nuisance case at a particular property.

By 2018, new language further expanded the list of reasons a property could be considered a public nuisance: code enforcement officials can now also consider misdemeanor drug crimes, possessing drug paraphernalia, theft, sexual offenses, and unlicensed massage therapy as the basis of a nuisance case.

Though much of the public discussion of the ordinance has focused on hotels, motels, and troublesome convenience stores, it’s almost always used against residential properties, the KyCIR review found. About 84% of cases are in the county’s western half, where studies show residents are more likely to be poor, black, or disabled, and less likely to own their home.

Green, the councilwoman, said she refuses to believe that nuisance crimes are largely occurring only in homes in west and southwest Louisville.

“Who is doing the screening process?” she said. “Who gets to ride off into the sunset because they check the box of being affluent, white, East End?”

When LMPD officers suggest possible nuisance cases, resource officers from each division screen them and pass them on to code enforcement. Louisville Metro Police Sgt. Christina Beaven, who until recently was the First Division Resource Officer, which includes portions of west Louisville, said the expanded ordinance was a “huge win” for LMPD. Nuisance cases actually allow them to help citizens in poorer areas of the city, where absentee landlords might ignore problem tenants, Beaven said.

“It’s not fair that they can’t have the quality of life we have in other parts of the city,” Beaven said. “Nobody would ever put up in the East End with having a drug house move in next door to them.”

But one expert on nuisance ordinances said this ordinance as written could be having a disproportionate impact in neighborhoods where police are more present.

Megan Hatch, an associate professor at Cleveland State University's department of urban studies, researches nuisance ordinances, and she reviewed Louisville's public nuisance ordinance at KyCIR’s request. She noted that it allows broad enforcement for nearly any run-in with police — and not just for arrests and confirmed crimes, but any time a police report is written.

A police report can be written for nearly anything, Hatch said.

"This is a little harsher than some," she said.

And it’s unclear what leads one property to be considered as a nuisance over another with a similar history.

In October 2017, police filed an incident report after responding to the scene of a shooting in the Parkland neighborhood. The victim became “uncooperative” after he was confronted with inconsistencies in his account, according to the incident report, and he refused to participate in the investigation.

Later that month, he received a letter informing him of the nuisance violation.

When asked if a nuisance violation is used as an added penalty when people don't want to cooperate with police, Halladay of LMPD said it’s useful to force the hand of a landlord who isn’t willing to make changes.

“Not everyone willingly wants to fix an issue,” Halladay said. “Public nuisance is designed to say, 'Hey, what's going on here isn't acceptable by this community’s standards because we passed the law on this and we would like you to make some changes, or there will be some penalty.'”

Relying on nuisance laws to counter some of society's most pressing issues is misguided and shortsighted, said Marie Claire Tran-Leung, a senior attorney with the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, a Chicago-based economic advocacy group.

“It's not a way to actually address problems that are in a community,” she said. “It's just a way to sort of put a Band-Aid on things.”

And it could cause some vulnerable people to be unwilling to call police when they need help.

Advocates: Eviction Threat Could Stop Victims From Seeking Help

Elizabeth Wessels-Martin, the president of the Center for Women and Families, said she was unaware that the city’s nuisance laws were being enforced after domestic violence incidents.

It’s unrealistic, she said, to expect victims to bear the burden of resolving a nuisance case.

“Domestic violence relationships are very complicated and very intertwined,” she said.

Some victims may depend on their abuser for financial support, or perhaps they fear their children may be taken away if they report abuse, Wessels-Martin said.

Adding the threat of eviction could absolutely prevent victims from seeking help, she said.

"It pushes victims to stay with the perpetrators because they don't have anywhere else to go," she said. "They don't want to be homeless."

In Louisville, the number of people experiencing homelessness due to domestic violence has increased steadily since 2014, according to research from the University of Louisville's School of Public Health and Information Sciences.

In 2018, more than 1,580 people spent time in a homeless shelter due to domestic violence, which is a 17 percent increase compared with the year prior.

LMPD and codes officials said they would consider revisiting the issue as it pertains to victims.

Kirchdorfer of the codes department said he didn’t know his department was using the nuisance ordinance against victims of crime, particularly domestic violence.

“I think on these, we need to have some further followup with LMPD,” Kirchdorfer said. “We don't want to cause any problems if someone’s been victimized.”

Austin, the supervisor of the nuisance program, said he reviews each case before issuing the violation notice to ensure the charges qualify as a public nuisance.

Domestic violence incidents can qualify a property as a public nuisance, under the ordinance, because all assault-related offenses can be considered a nuisance. But Austin said he’s never approved a notice in a domestic violence case since he took over the role in May. Records show his office has, before and since Austin’s tenure.

Halladay, the LMPD spokesperson, said the enforcement “may have some adverse consequences for those people who get caught up in other people’s behavior.”

“If we need to review how domestic violence has been impacted... we’re totally open to that,” Halladay said. That is not our intention, to put people in a position of greater hardship.”

With Little History Of Problems, Families Surprised By Notices

Andrea Swain was out of town when her cozy, tidy Shawnee home was labeled a public nuisance.

Swain is a homeowner, and she likes the neighborhood, close to downtown and the interstate. She recently replaced the hardwood floors, and photos of family line the shelves. On the wall near the front door is a framed, old newspaper article featuring her son when he was younger, with a violin tucked beneath his chin.

“We’re just a normal family,” Swain said. “We get up and take care of our yard and talk to our neighbors. We are not a nuisance.”

She was visiting family out of state when the police showed up to her house in March 2018. In her absence, her son, then 17, had friends over for a night of socializing and smoking weed.

One of the teens grabbed a pistol and fired it into the dirt in the backyard.

Swain’s house is on a street equipped with ShotSpotter, a gunshot detection system largely reserved for the city’s highest-crime blocks. The police showed up, and cited the teens for possession of marijuana. Swain’s son was cited for possessing the gun as a minor.

Two days later, the city sent Swain a letter, informing her that her home was a public nuisance because of the incident. Swain doesn’t condone what her son did, but she’s also not sure how that one incident qualifies her home as a nuisance.

But it’s allowable under the ordinance, which requires two police interactions within 12 months. Police records show they had visited Swain’s home on three different occasions. Twice, they came in response to burglar alarms. The other time, they were asked to make a welfare check on Swain, who suffers from lupus and brain cancer, after she missed a doctor’s appointment and didn’t answer the phone.

Since Swain owns the home, she’s not at risk of eviction. But she risks a $400 fine if the police are called to her home again.

“I would be highly pissed if something like that happened,” she said. “Four hundred dollars is a lot of money.”

The threat wouldn’t necessarily deter Swain from calling for help, if she needed to. But she doesn’t think it’s fair.

Far down Dixie Highway, beyond the strip clubs and factories, Kenneth Allen Sr. lives in a 700-square-foot home built on the steep bank of the Ohio River. There are no other homes in sight, but his home has nonetheless been deemed a public nuisance, too.

This February, Louisville Metro Police and the United States Postal Inspection Service showed up at his door for a “knock and talk,” according to police records.

They alleged that Allen, 79, trafficked in controlled substances after they seized eight pain pills he tried to mail to his son in Florida.

Allen couldn’t be reached for comment. His wife, Diana Allen, said she thought the nuisance violation was unwarranted, and amounted to police harassment.

Allen’s landlord, Ted Hayes, received a letter alerting him that the property had been deemed a public nuisance, and noting that a defense to the violation would be evicting Allen. He refused.

“Why would you evict someone for that?” Hayes asked. “The man wasn’t dealing drugs out of my property. [The police] know that, he’s not a drug dealer.”

Hayes received that letter shortly after Allen was charged — well before Allen’s trafficking charge was amended down to not keeping his prescription pills in the proper container.

Hayes had his attorney send a letter to the code enforcement department letting them know he was not going to evict Allen. He said he never heard anything else.

Landlords Say Enforcement Is Complicated For Business

Enforcement is complicated for property owners, who might welcome the added information from law enforcement but are also trying to run their private business as they see fit.

“I like to know what’s going on,” said Lisa Thornton, who manages nearly 40 properties in the city, three of which have been deemed a public nuisance.

In October, at a house she owns in southwest Louisville, police arrested a 24-year-old woman for possession of methamphetamine, according to police records. After receiving the notice of the public nuisance, Thornton contacted the tenant — the arrested woman’s mother — to find out what happened.

As Thornton tells it, her tenant’s daughter was visiting, and when she refused to leave, the tenant called the police to escort her out. She had outstanding warrants, and the police arrested her. Then, they found meth on her, and issued a nuisance violation against the house where her mother lived.

Thornton decided not to evict the woman she called a wonderful, long-term tenant who keeps her house clean.

But Thornton said she doesn’t want to be perceived as a landlord “that turns a blind eye.” So she told her tenant her daughter was no longer permitted to visit — even though the tenant is caring for her daughter’s child.

“I like to go by the law,” she said.

Toni Raybon owns a handful of properties in western and southwest Louisville. She said it’s unfair to saddle landlords with potential fines if tenants fail to adhere to the city’s standards.

So when police served a search warrant in October 2017 on her tenants and found drugs and guns, Raybon promptly evicted. She felt like doing so was her only option.

“I don’t want to be associated with that,” she said.

Richard Sturgeon was glad to receive a public nuisance violation on a home he used to own on Blue Lick Road in far south Jefferson County. He said he suspected his tenants were dealing drugs, and he was quick to evict after LMPD charged the man with trafficking methamphetamines.

“It gave me an excuse to get rid of them,” he said. “You can’t blame me for idiots like that.”

The ordinance also wields power over property owners who live in their properties.

Police asked codes in March 2018 to issue a nuisance violation to a home on West Madison Street. Beaven of LMPD said its occupant was one of the most notorious drug dealers in the Russell neighborhood.

“We all knew he was dealing drugs,” she said. “Because of the public nuisance ordinance, we were able to dislocate him from that area.”

But, property records show that he was not exactly pushed out — at least not immediately.

In the midst of the case, he bought the house from his landlord.

He was cited, and then codes issued him an “order to vacate” in February — he wasn’t allowed to live in the house he owned. Or, at least, he wasn’t allowed to live in that house: property records show he owns three others, including one on the same block.

Eviction doesn’t necessarily resolve the problem, according to Hinko, the housing advocate.

“It's just a waterbed,” Hinko said. “You push down here, it rises somewhere else. People are just moving around, because you're not intervening in a meaningful way.”

Rules Unclear Even To Enforcers

According to Louisville’s ordinance, properties are considered a nuisance after two incidents with police within a year.

Code officials are supposed to issue a warning after the first notification from police, notifying the property owner that “further violations will constitute a public nuisance.” After a second report from police, code officials should notify the owner that the property is a public nuisance — and that the public nuisance must be abated. If it isn’t, property owners risk fines or even an order to vacate.

But interpretations of that ordinance vary depending on whom you ask.

Beaven, the LMPD sergeant, said just one visit from police can result in a public nuisance violation — but LMPD officers wouldn’t do that “arbitrarily,” she said, unless they knew there was a problem.

Austin, the Code Enforcement supervisor, said “there is no set number” of incidents needed at a property to trigger a nuisance violation.

But the ordinance clearly mandates that a property must be the site of at least two police incidents within a year before it can be considered a public nuisance.

Austin said he doesn’t know how many runs LMPD has made before they ask his office to issue a violation, and the violations only include detail about the one police interaction that led to the violation.

“We just go by what LMPD sends us,” he said.

While Kirchdorfer of the codes department said the letter his office sends is indeed a warning, as the ordinance prescribes, the letter specifically says the property has been deemed a nuisance and offers eviction as a defense, a review of the records shows.

Louisville City Council President David James didn’t respond to a call for comment. Green, the chair of the council’s public safety committee, said city employees need to understand the ordinance language — and follow it.

“If we have employees out there that are violating what the code says, shame on them,” she said. “They should be dealt with.”

But the confusion extends all the way through the appeals process.

Dozens of police officers scaled Charles Barbee’s fence in June 2018, rifles in hand, looking for signs he was selling drugs.

The police found no drugs inside his Pleasure Ridge Park home after executing that search warrant. But records show police found weed and two guns in a truck in the driveway.

Barbee is a felon, and he was arrested and charged with illegal possession of a handgun, trafficking marijuana and possession of drug paraphernalia. He spent the night in jail. Three weeks later, city officials sent his landlord a public nuisance violation notice.

Barbee’s landlord is his son, Andrew Barbee. He appealed, using the process laid out in the registered letter he received.

Records show he’s one of only about a dozen property owners to take that step, since that’s how many cases the city’s Code Enforcement Board has reviewed out of nearly 500 nuisance cases since 2017.

The penalties laid out in the violation letter are also rarely enforced: only 25 of the cases have resulted in a $400 fine, records show. Five were eventually issued an order to vacate.

In February, Andrew Barbee’s attorney, Stephen Ryan, argued to the enforcement board that the charges against Charles Barbee weren’t lawful.

Jeremy Kirkham, the board chair, questioned how the property could even be considered a public nuisance.

Only one incident involving police was listed on the violation notice, and the ordinance requires at least two. Kirkham turned to Wesley Barbour, the Code Enforcement official present at the hearing, to explain how the case met the definition of the ordinance.

Barbour fell silent, and searched the ordinance for nearly two minutes. Then, he said the notice is only meant to alert property owners that an additional incident involving police would constitute their property being listed as a public nuisance.

The letter Andrew Barbee received clearly stated the city “has deemed your property … a public nuisance.” It made no mention that at least two incidents with police are required before a property can be considered a public nuisance. And an unknown number of landlords have evicted their tenants on the basis of similar letters.

Upon hearing Barbour’s explanation, Kirkham ruled the Barbees were never deemed a nuisance in the first place. They had nothing to appeal.

Ryan, the attorney, said he and his client would be satisfied — although, he noted, “I don’t really understand.”

The Code Enforcement Board chair laughed.

“Apparently we don’t either,” he said.

Caitlin McGlade contributed to this report. Contact Jacob Ryan at (502) 814.6559 or jryan@kycir.org.